Food Deserts in Alachua County

Background

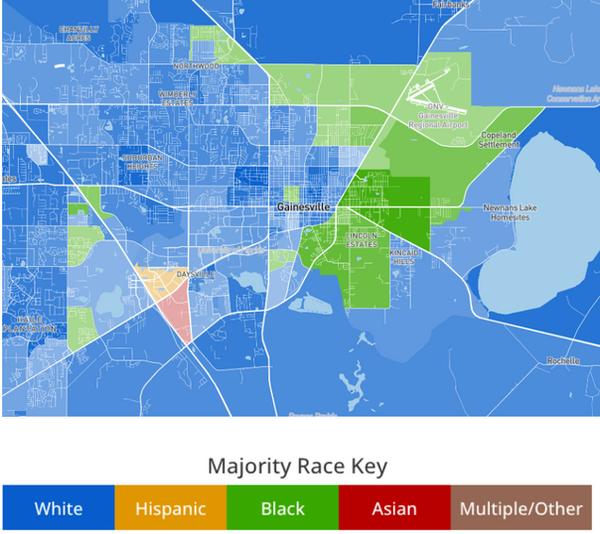

Food deserts are defined as geographic areas where residents have limited access to affordable and nutritious food, particularly fresh fruits and vegetables. These areas are frequently located in low-income neighborhoods where residents often lack transportation options, compounding their limited access to grocery stores. This project focuses on identifying and analyzing food deserts in Alachua County, Florida, using GIS tools to illustrate patterns of food insecurity. Special attention is given to East Gainesville, a predominantly Black and low-income area where access disparities are especially pronounced. The research reveals how historic patterns of segregation, economic disinvestment, and urban planning have spatially entrenched food insecurity in these communities.

Research Sources and Methods:

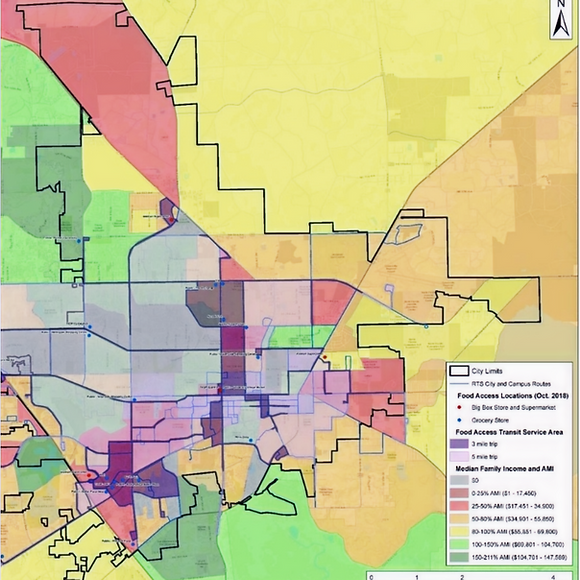

This project utilized spatial data from the USDA Food Access Research Atlas (2020) to identify census tracts classified as food deserts. Demographic data from the U.S. Census Bureau, including income levels and racial composition, were layered using GIS analysis to visualize correlations between poverty, race, and food access. Additional secondary sources included Babb et al. (2012) on historical mapping of Alachua County food deserts, local news reporting from The Alligator (Allen, 2022) and WUFT (Tanen, 2015) regarding community concerns and grocery store development patterns. Florida Department of Health Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (2022) data was also incorporated to link food access to obesity rates. GIS techniques such as spatial joins, buffer analyses (e.g., one-mile walking buffers around grocery stores), and demographic overlays allowed for a comprehensive mapping of food insecurity hotspots. Ethnographic data was gathered through community interviews and reports highlighting resident experiences of food hardship.

Summary of Key Findings:

The GIS mapping identified 11 census tracts in Alachua County as USDA-classified food deserts, with a majority concentrated in East Gainesville. Babb et al. (2012) found similar patterns a decade earlier, demonstrating little progress in mitigating food insecurity. Ethnographic reports and interviews with East Gainesville residents documented significant struggles, such as reliance on convenience stores for groceries and the financial burden of traveling several miles to reach a full-service grocery store. Residents expressed frustration with both private grocery chains, which preferred to open in affluent west-side neighborhoods, and policymakers who had not incentivized grocery development in underserved areas. Local journalism, such as Allen (2022), confirmed that transportation barriers and racial disparities exacerbate food access problems. Health data from the Florida Department of Health (2022) revealed that 65.6% of Alachua County residents earning under $25,000 annually are classified as obese, reinforcing the connection between poverty, limited food access, and negative health outcomes. Spatial analysis visually confirmed that areas with predominantly Black, low-income populations faced the greatest food access challenges.

Figure 1 - an outline of economic demographics by population tracts in the greater gainesville area

Figure 2 - an outline of racial demographics by population tracts in the greater gainesville area

Conclusions

GIS analysis clearly illustrated the spatial injustice underlying food deserts in Alachua County. The evidence demonstrates that these areas result from a legacy of systemic inequality, where historical segregation and patterns of urban development favored investment in affluent, predominantly white neighborhoods while neglecting communities of color. A major challenge in this project was the limited availability of granular, up-to-date GIS datasets, requiring triangulation with ethnographic and journalistic sources. Another limitation was the difficulty of accounting for informal food sources, such as local produce stands or mobile markets, within formal spatial datasets. Despite these challenges, the project shows that addressing food deserts requires not only spatial analysis but also policy reforms focused on economic incentives, equitable urban planning, and community-based food initiatives. Proposed solutions include supporting local food cooperatives, subsidizing grocery development in underserved areas, and improving public transportation links to food retailers. Without targeted interventions, food deserts will continue to reflect and reinforce broader patterns of inequality.

References

Allen, M. (2022). Food insecurity persists in East Gainesville. The Independent Florida Alligator. Retrieved from https://www.alligator.org

Babb, C., Feagan, R., & Tait-Neufeld, S. (2012). Mapping Food Deserts and Food Swamps in Alachua County: Community Analysis and Recommendations. University of Florida Food Systems Report.

Florida Department of Health. (2022). Florida Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Report. Retrieved from http://www.floridahealth.gov

Tanen, M. (2015). Grocery stores thrive in West Gainesville but leave East Gainesville behind. WUFT News. Retrieved from https://www.wuft.org

USDA Economic Research Service. (2020). Food Access Research Atlas. Retrieved from https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/